Safe At Last

Remember this?

It's been living in our downstairs hallway since before anyone can remember. I've now met 3 prior owners of our house, and none of them has been able to offer any more information on it than "I've never seen it open and I've never seen the key." It's been a continuous elephant-in-the-room for generations, bearing numerous signs of hammer-attempted forced entries, a source of mystery for decades.

Well, no more.

Meet Bob. (Bob, due to the somehow sketchy possibilities of the nature of his profession, asked that I not photograph him, so I clandestinely snapped this photo of his trainers... it'd be enough for any competent forensics CSI to go on, surely):

Bob is a safecracker. You see, the company that made the safe is still in business, and for a fee, they'll bust into your safe for you. There's no guarantee that, once open, they'll be able to re-lock it or even repair the newly broken lock. Not until we look inside will we know what's really going on there.

But after nearly two years of wavering (safecracking isn't cheap), we've decided to go for it. It comes down to the fact that we have a few things to protect, mostly backup drives and the like, which are a thousand times more valuable to us than the price of Bob's services. We're hoping that, even if the safe's internal mechanisms can't easily be repaired, we might still somehow contrive to use the thing. If that means a padlock and a hasp on the outside of the door, that's ok. I just want a hearty secure box for hard drives and documents.

And who knows what juicy lucre might be concealed within? The contents of the safe might even pay for their own liberation. Well, I can hope.

And so to work:

Bob's first reaction when he laid eyes on the safe was a cool low whistle. "This is an old one," he said. He retrieved from his car a book of all the safes made by Fichet, dating all the way back to 1915. Some incredible things in there, too. In the 20's they were making beautifully scrolled and carved elegant wooden furniture, just like any other beautifully scrolled and carved end table or dresser, except with strongboxes concealed within. Cool. Each safe was pictured, and came accompanied by a description of how the mechanism worked, and where the bolts could be located. But alas, our safe apparently predated the book. It was not to be found.

So next Bob tried tapping all over. Without much luck, it seemed, at least from what I could tell. He wasn't using the classic stethoscope method or anything, but it all just sounded like the same tap tap tapping to me. Then out came the xray film. Not to take an xray mind you, but only to slide in between the door and the box, to try and discover how this safe works. Pretty cool. Like he could jimmy the lock or something with a flimsy sheet of plastic. After a while of doing this, Bob came to an important conclusion, and one which it's safe to say came as a great surprise to me: the safe was not locked.

"What?" I asked him, "Not locked?"

"Not locked," he repeated.

It seems that there are two independent mechanisms which can hold the door shut. One, of course, is the bolts themselves. Several of them, cylinders, jutting outward into their sturdy doorframe receptacles. But these were not doing so. The bolts were, apparently, still nestled within the door. Leaving only one small obstacle holdiong the whole thing shut: the latch, the beveled bolt connected not to the lock, but to the knob. Just like on a regular door. And the latch was stuck.

So how do you fix this? Simple enough: use a hammer! Bang bang bang, and POP! The door jumped open. It was an incredible moment.

The moment of truth. What had been lurking inside all this time?

So exciting.

Of course the first thing that struck us was the existence of plastic bags. Plastic bags containing what looked like hand-upholstered and -embroidered pillows.

The pillows bore what looked like dry-cleaning tags, or maybe price tags. Hard to tell. But the bags they came in were more interesting. A Mammouth carrier bag. Mammouth was a chain of French hypermarkets, which first opened their doors in 1966. 30 years later, they merged with another chain and became what is now known as Auchan. Hmmmm. So we know that the safe was open relatively recently. But why use it to store pillows?

And then above the pillows was a hefty stack of aging documents. Here's the real goody-bag. they were old. With beautiful scripty writing on lots of them. We found birth certificates, death announcements, baptism documentation, primary, high-school and college diplomas. We found letters from the Ministry of War from the 20's. A single-page, valid-for-one-year passport. Family photos. Personal letters. Incredible, with dates ranging from 1840 to 1946.

From what we can tell, a Swiss fellow named Ernest Rayroux had joined the French military during WW1. He was then granted residency here, and moved to Montcaret. Somehow, perhaps through marriage, the house then passed into the hands of the Bach family. One of them was the Pastor of the local protestant temple. they had generations of kids here. Lots and lots of documents.

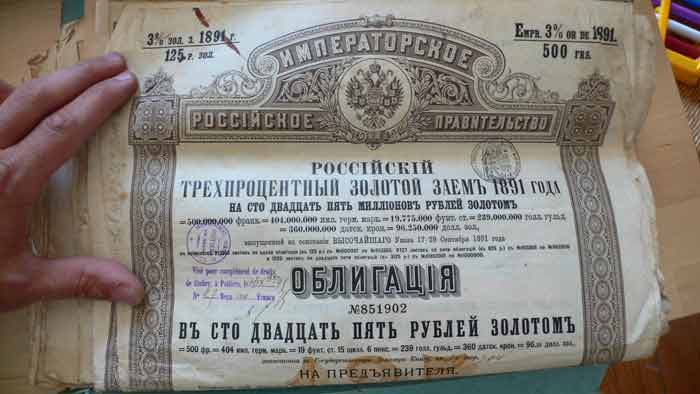

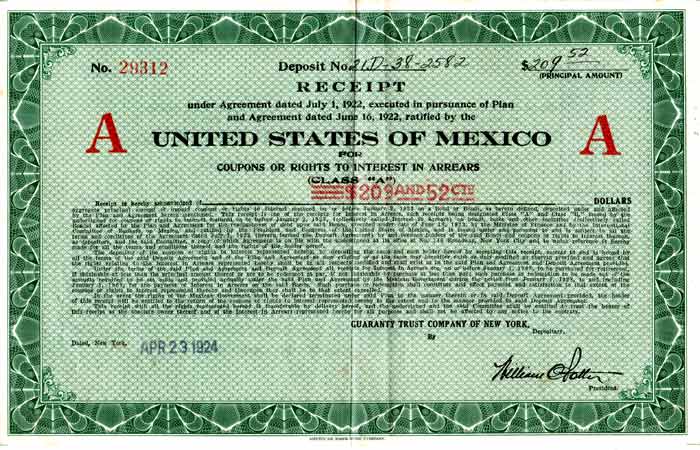

Also, we found financial documents. Insurance from the house back in the day, but more interestingly, bonds. A huge stack of Russian 3% and 4% bonds from 1898-1908. A bearer-bond from "The United States of Mexico" dated 1924 in the amount of $209.52, issued by a New York bank. Beautiful old things.

But I'm getting a little ahead of the story, I fear. Because Bob was still there, and I didn't have time to go through everything right away.

We emptied the safe, and were unable to find a key. Bob told us that that happens a lot, actually, the key getting locked inside. Then he took apart the door to see how it all looked in there.

Cool, eh? You can see better here: the five big bolts had not been thrown. only the little cylinder on the spring, second up from the bottom on the right, had gotten stuck in the out position. So Bob removed it for us.

Now we have a safe which doesn't lock. We can easily set the bolts in and out with a simple turn of the door handle, but we can't actually lock it in either position. Bob says that to make a new key to fit the old locking mechanism would cost somewhere around €1500, which is more than the price of a new safe. So we're left with a very cool, very heavy cupboard. I can live with that. --And a lot of documents.

So what about those documents?

Well, the Russian bonds are clearly not going to be worth much at face value. There was something of a Marxist revolution in Russia, from what I understand. As far as collectibiility, I have no idea. My dad knows a trader in vintage bonds, so I've sent along some pictures for him to look at.

The Mexican bond might actually be worth something. Mexico still exists, of course. Who knew it was formally still called The United States of Mexico? And The Guaranty Trust Company of New York, as it turns out, has since evolved into a little outfit called JP Morgan. I called them, and after explaining my situation to several people who had no idea what to make of it, eventually found my way to their research department. They have a research department. Sweet. Send them a copy, they said, they'll let me know. $209.52 was a lot of money back in 1924.

And then we ran into Josette, Helen's neighbor in the village. Helen's house used to be the Montcaret bakery. They still have the giant and beautiful bread oven in their future living room. And Josette grew up in that house. She's somewhere around 80 years old, and when we mentioned to her that we had all these documents, she started telling us all sorts of stories about the Bach family. She even drew out a four-generation family tree. Sweet. And, as it happens in villages, there are still some great-grandkids living in the area.

So Josette has put us in touch with them so that all these family documents can be returned to their proper owners. They're interesting, and they're historical, but they're not ours. I hope they are properly pored over and appreciated. The lady called me, and she'll be round next week to have a look.

We're also planning on giving them the bonds, whatever their value. If it does turn out that any of them are still worth something, we might ask to be reimbursed just for the safecracking fees. But it's not our money.

It has been quite an adventure, though.

And if you look carefully at the first picture at the top of this entry, you'll see a separate panel with a keyhole along the bottom front of the safe. Yep: nestled within the pedestal is an entirely separate lockbox. The only way to get into this one is with a disc cutter. Maybe one day we'll do it. But until then, at least we still can enjoy a bit of the mystery the safe has been providing to so many people for so many years.

I wonder what's in it?